But words and books have little place in his world—shocking for a grandmother who has read and continues to read copiously every day of what is becoming a rather long life. My stance is ‘Reading is how humans pass on knowledge’, each generation building on their ancestors’ knowledge to expand and deepen our grasp of the interior and exterior world—each generation standing on the shoulders of past generations to understand a little better life on planet Earth and beyond. Even though his world is dominated by mathematics, his humanity demands that he navigate the wordy realm—I rest my case.

And so it began.

I grew up on a farm, 5½ miles from a village of about 400, 85 miles from the closest city of about 10,000. The big city, Regina with a population of about 100,000, was 200+ miles beyond that, which may as well have been overseas for ease of access in those days. In other words, I grew up in the middle of nowhere in 1950s Saskatchewan, with not many ways to spend the few precious hours snatched from the relentless work of life on a farm.

But I was lucky because I was eighth in a family of 11 children, and we loved to read. So all I needed was a book, and my imagination did the rest.

I can still feel the warmth and deep joy of snuggling in on a rainy afternoon listening to an older sister read The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn and The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. We’d all be crowded onto the bed in the summer kitchen next to the row of batteries & generator for our private 32-volt electrical system. The thrum of the motor and the warmth it generated was the perfect background for the enthralling story of Huck and Tom.

Then my brother and I formed our own little Huck & Tom society with secret forts and rituals, officiously excluding all others. Only a younger sister longed to be part of our group—our older siblings had neither the time nor desire to participate in this conspicuous juvenility—and we tormented her accordingly: We’d promise her entry if only she did …, and then add another condition and another. She never did get to join, but she has lived a successful life, making far more money than either of us. So there’s that.

(Hydro, as the public electrical-power system was called, didn’t reach our area until I was in high school. Mom campaigned hard for it, driving all over the countryside to persuade the neighbours to step into the modern world of light at the flick of a switch, many of whom thought it a high-falutin’ luxury for soft city folk! Primitive, eh?)

Another favourite of the family reading hour was Pat of Silver Bush by Lucy M. Montgomery. It’s a story of family and home, both of which Pat loves deeply, dreading the inevitable changes life brings. Pat was 7 years old at the beginning of the story, my age, so I lived her love of the sweetness of the familiar and her dread of the outside world. The green cover became faded and the pages worn with our constant re-reading of the book. Then I turned 10 and discovered Anne of Green Gables with a heroine much more adventurous and rebellious, therefore, a much more fitting role model, I thought. But Pat will always have a special place in my heart, a beacon of my love of family and home that is central to my life.

The floodgates open.

The thrill of being read to very quickly led to learning to read. Because books weren’t abundant and children’s books were nonexistent in our house, I just started to read whatever came to hand: the newspaper, The Western Producer; pamphlets on farm machinery & practices, entries in a 14-volume encyclopedia a traveling salesman sold to Mom in a weak moment. The motherlode was a bookcase, five shelves and about 5 feet tall, filled with books Dad had collected over his reading life. It was an eclectic library and I consumed it all.

Fyodor Dostoevsky. When I was 11, I picked up Crime and Punishment, and the door opened wide to the why of life and stayed open. The book must have belonged to my oldest sister, who read constantly much to Mom’s annoyance because she was often not there when work had to be done. I can still see it: a well-thumbed paperback with the title in red & black letters on its ivory cover (maybe a Penguin edition?). The pages were thin and the text small, demanding the reader’s close attention for its 450+ pages. The story of Raskolnikov deeply impressed me, and I continued on to Dostoevsky’s trail of sin and redemption in The Brothers Karamazov, The Idiot and Notes from Underground.

Leo Tolstoy. It was many years later that I read another Russian giant’s masterpiece, War and Peace. By that time, of course, the story was familiar and the movie was seen. Nevertheless, reading the behemoth of a book—at some 1,400 pages—takes concentration and dedication, rewarding the reader according to her attention paid. Long before that, I had read Anna Karenina to great reward in understanding affairs of the human heart a little better.

In both novels, Tolstoy uses a French proverb, “Happy people have no history” to counter the delusion “…that true life is lived at times of high drama…Tolstoy thought just the opposite,” as Gary Saul Morson in “The Moral Urgency of Anna Karenina”, Commentary, April 2015, cogently argues. Romantic love as the pinnacle of love is the prevailing sentiment in our culture, epitomized in Romeo and Juliet, “…but Tolstoy wants us to recognize that romantic love is but one kind of love” and “…only intimate love is compatible with a family.” The choice between romantic love and intimate love exists for Anna and for everyone of us, is Tolstoy’s theme in both these novels, Morson contends and I agree.

Like so much of the prevailing wisdom, the worth of the different types of love is upside down. Romantic love is portrayed as the state devotedly to be wished, an uncontrollable passion that we fall into and are consumed by; intimate love, the kind that sustains a marriage and raising children, is derogated as bourgeois and banal. “Anna’s story illustrates the dangers of romantic thinking. As she gives herself to her affair, she tells herself that she has no choice, but her loss of will is willed,” Morson writes. ‘Loss of will is willed’ is the perfect explanation of the easier, morally inferior choice that Hollywood gives the Oscar to.

BTW, Morson’s essay is insightful, probing and illuminating—exactly what students should expect from their humanities professors. But it is sadly lacking in this postmodern era of humanities diminution by victimology studies of every sex and colour. How lucky his students at Northwestern University are!

And so my rich reading journey began. Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights spoke to the romance in the teenage soul: What girl could possibly resist Heathcliff and his dark handsomeness with that touch of menace that sets the heart aflutter? And Catherine’s discovery of her soulmate on the wild Yorkshire moors spoke to the teenage idealism that just knows there is only one other who will complete her. While our east and west pastures were not quite as wild as the moors, we ‘wild’ siblings imagined them so, building secret forts in the dense trees of the east pasture (that Mom would discover that evening or the next morning when she went to get the cows for milking) and rafts to sail on the huge ponds that formed each spring when the snow melted in the west pasture. Catherine & Heathcliff’s fierce love of each other attracted and repelled, haunting the reader with its joy and inevitable tragedy.

Then it was on to her sister Charlotte Bronte’s opus, Jane Eyre, followed by Thomas Hardy’s dour, but intriguing novels, Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Jude the Obscure, The Mayor of Casterbridge, The Return of the Native, followed by Jane Austin’s lighter, but intricate novels, Pride and Prejudice and Emma—some studied, all enjoyed. In fact, not one of the many novels I had to read for my English degree did I not enjoy, often feeling a little sad to leave that world as I read the last word.

The American plank of the foundational stage of my literature love affair was built on the novels of Henry James (Portrait of a Lady, The Ambassadors), Theodore Dreiser (American Tragedy), Edith Wharton (Ethan Frome, The House of Mirth), Willa Cather (My Antonia), William Faulkner (As I Lay Dying, The Sound and the Fury). Oh, to be young and discover them all again!

The darkness enters.

Darkness at Noon, by Arthur Koestler, aptly introduced the dark stage in my reading regimen. Its story of communism eating its own in the Moscow show trials of the late 1930s is bleak—but not bleak enough to disabuse Western intellectuals’ of their love of all things far left. The excuses they keep making—Jean Paul Sartre kept it up all his long life, collaborating with the Nazis when they occupied Paris and defending communism when Lenin, then Stalin outdid Hitler in the killing fields—are sickening and contribute to the disgust many have today for experts of every ilk. George Orwell’s 1984 and Animal Farm and Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World exposed the totalitarianism that government overreach, central planning and regimentation inevitably lead to. (It’s comical, if it weren’t frightening, how today’s progressives try to skew the message to criticize conservatives defending our Western democracies from the very socialism/communism portrayed in these books.)

In this exploration of man’s inhumanity to man I discovered some of the greatest writers of MittelEuropa: Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities, Joseph Roth’s Radetzky Waltz, and Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain explore the dying days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire civilization as it is consumed by the barbarism of Nazism and communism. By grand German civilization I read on and wept—to paraphrase one of my favourite titles, By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept by Elizabeth Smart, and a good book it is, too—as I witnessed the destruction of this civilization by the malicious evil of Hitler & Co, and by the inattention of so many Western liberals.

Short stories fill the cracks with light.

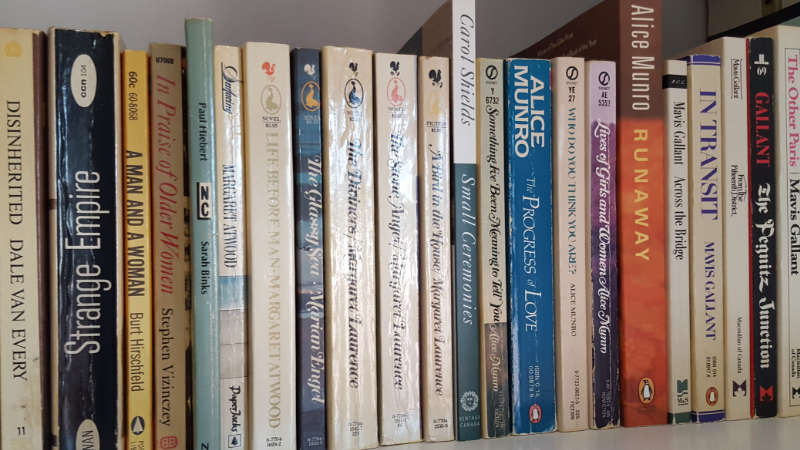

Many of the stepping stones out of this darkness were short stories—superb short stories written by the best: Canadians Mavis Gallant and Alice Munro; American Flannery O’Connor; and Irish William Trevor. I highly recommend all of the stories by every one of them. And their short commitment lends itself to today’s busyness, where a commitment of more than a few hours of one’s time is considered an affront to one’s importance. I am happy to have one of these still left in my treasure chest of unread books, the aptly named Last Stories by Trevor, which I’m saving for my Christmas 2019 wish list. And rereading short stories is a happy interlude in the midst of reading a hefty tome.

In the midst of the dross of current writers—so many of whom are infected with the disease of the privileged, identity whining and virtue signaling—I discovered two gems.

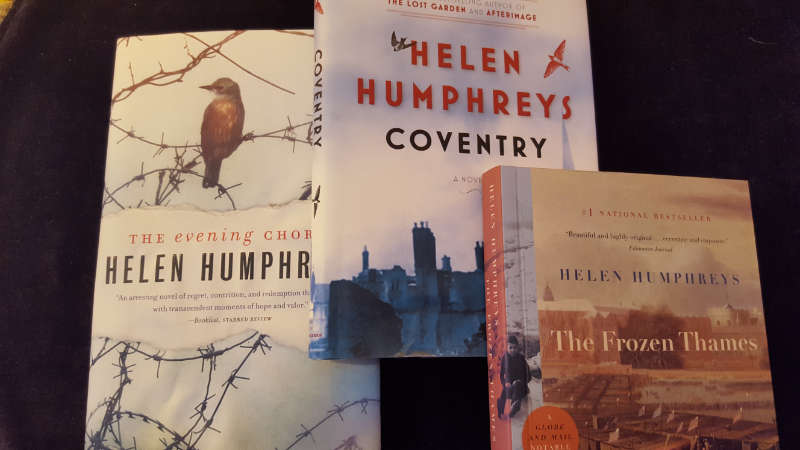

Helen Humphreys was born in Kingston-on-Thames, England, and now resides in Kingston, Ontario, a neat symmetry of place for this poet and novelist. I read a review of The Frozen Thames, read the book and was captivated by her writing. It is about life on the frozen river, a collection of stories about the 40 times this has happened (an inconvenient truth in today’s every weather event—good and bad—being charged to the manmade climate-change account). It’s fascinating how Londoners adapted—and thrived—in these icy interludes, capitalizing on what the solid surface offered them.

Then I read Coventry and The Evening Chorus, both set in World War II England. The central event in Coventry is the Luftwaffe’s blitz of the city on the night of November 14, 1940, and the citizens’ courage as told through one woman’s help of a son to find his mother in that dark night of fire and brimstone. The Evening Chorus is the story of a British officer captured by the Germans who, at first to pass the time but soon in fascination, studies a pair of redstarts (birds) that make their nest just outside of the POW camp. The German kommandant shares his interest and an unlikely bond is formed between captor and captive.

Both novels embody two of Humphreys’ major themes: the resilience of the human spirit and the solace humans find in nature in times of exceptional challenge. And she does this by letting the characters live these themes, not by lecturing the reader about human resilience and love of nature.

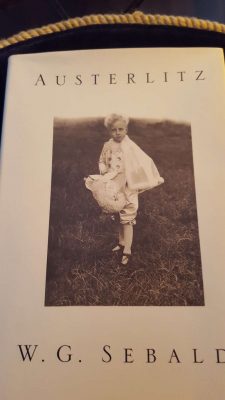

W.G. Sebald was born in Germany in 1944, and was educated in both Germany and England. When I read his books, it was often as if I were reading through mist, through the fog of memory. And blurry black and white photos add to that fog, illustrating the story only obliquely, indistinctly. Serious artists’ work resonates locally and universally, in their time and in all time. It is not surprising, then, that Sebald’s work, permeated with World War II, given his birthdate and nationality, still illuminates our quest for meaning. And it shines a little light on why the Germans chose their evil path.

I came upon his works in the usual manner, reading a review in the Literary Review, then another in the Times Literary Supplement. And also in the usual manner, once I discovered him, I tracked down his books and devoured them one after the other: Vertigo, The Emigrants, The Rings of Saturn and Austerlitz. With fact and fiction braided together in a silvery skein, they have that feel of MittelEuropa, that things are complicated, that humans are complex. But decisions and actions have consequences, and there is always a reckoning.

I anticipated joining Sebald on more journeys into his past and present, but it was not to be. He died in a car accident at the age of 57—still in his prime with so many more memories to make, and then explore.

Until the next ramble through my bookshelves…

This brings me to the end of the bookshelves in the master bedroom, with a few side trips into other rooms. Next time, I’ll ramble through the guest room’s bookshelves, then along a shelf in my office. After that, I’ll head downstairs to the den and living room. Oh, the fun of revisiting the books I have read!

And this—and the continuing rambles through my bookshelves—is my answer to friends and family who ask, “What should I read?”

I like to think of myself as well-read, but I have to admit I’ve shied away from the Russians. I shall give Dostoevsky and the Brothers Karamazov another go. I am currently reading a re-print of Hugh MacLennan’s, The Watch that Ends the Night (hmmm, I’m not seeing an option for italics in this format – perhaps your grandson would know).

I hadn’t really given MacLennan much thought. The book was originally published in 1959 and gives a fantastic view of the political climate and prejudices in force in Upper Canada in the years leading up to and after WWII. I love this edition because it provides a chronology for MacLennan’s life and a precise introduction to the book.

Yes, do read The Brothers Karamazov. Yes, it is long, dark and deep, in contrast to so many current novels that are short, light and shallow, but it is essential reading in my opinion.

Hugh MacLennan’s novels were my first look at the Canadian divide between Quebec and Anglo Canada (especially Ontario and the Maritimes). Being born and living on the prairies, I knew little and, to be blunt, cared little about their grievances. MacLennan is a good writer, thus a good way to be introduced to that divide and its effects on Canada.